Triangle of continuity: How artist S HarshaVardhana carries father J Swaminathan’s legacy forward

Published on 26/04/2025 09:11 PM

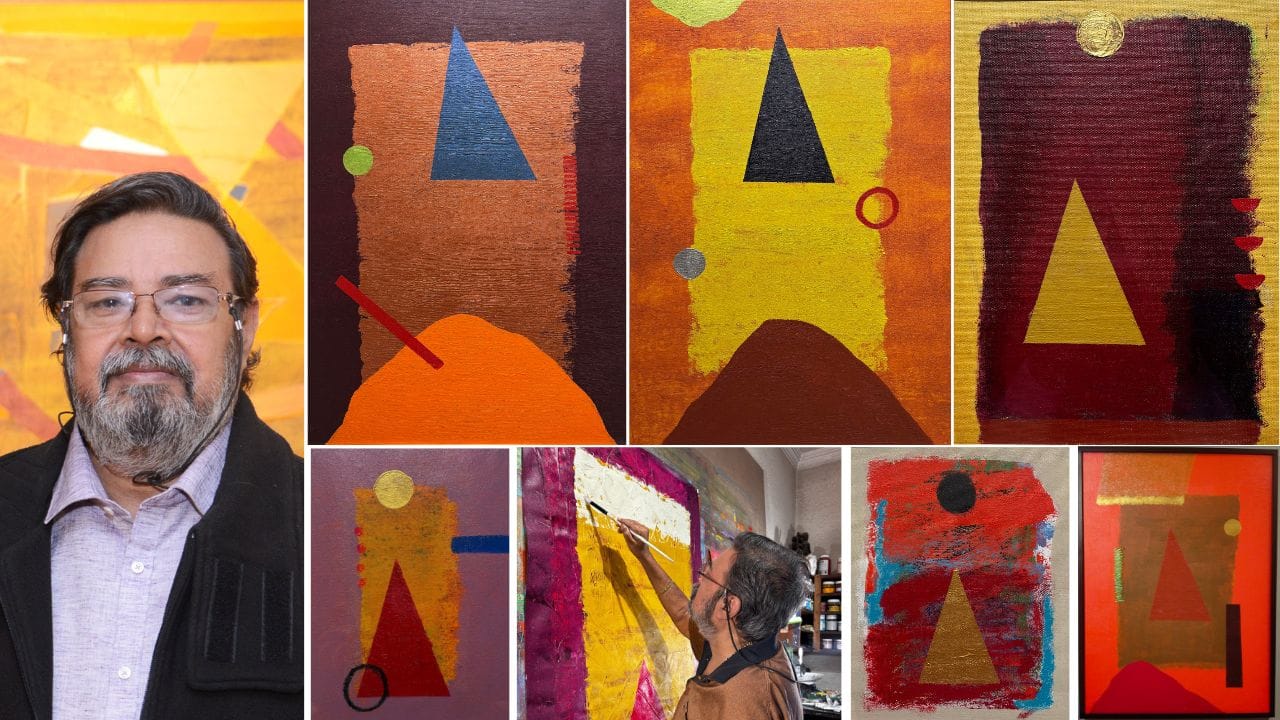

Jagdish Swaminathan, the seminal Modernist artist, poet, activist and advocate for tribal arts like Gond and Bhil, used to make a young S HarshaVardhana stand in his studio and clean the brushes and the rags he used for making art. “Every five minutes, in the middle of making an artwork, he would ask me, ‘kaisa lag raha hai? (How is it looking?)’ and I’d normally say, ‘achha hai (it’s good),’ then he would say, ‘tereko kya pata hai, chup karke baith (what do you know, go sit in a corner).’ That is the maximum kind of conversation we had,” says Swaminathan’s son. The boy stood there, perhaps, with a little innocent grudge towards the task he was assigned, observing his father consumed by the act of painting. One shape from his father’s early geometric brush paintings that must have stayed on in his psyche is the triangle.

The triangle finds pride of place at Delhi’s Art Alive gallery where HarshaVardhana’s latest solo show “Subliminal”, on till May 20, marks a fresh chapter in his artistic journey — of using bold colours. A lot like his father.

Late artist J Swaminathan (left) and his son S HarshaVardhana.

Here is a blue right-angled triangle is floating up, there is a dark brown isoceles triangle stands suspended but firm like a nose on a face, a circular red ring on side of its colour field is like a nose-ring while a silver circle on the other side is like a mole above the mouth from which emerges an inverted tongue — which looks more like a mountain. Or it is a mountain looking at the sun and moon gyrate around the other peak which is the triangle. In another similar painting, a red rectangular cigarette-like stick juts out of the orange mountain-like mouth. In yet another, an abstract Devi’s (goddess) face-like image where many hues meet — brushstrokes of orange, red and sky blue — as a black circle sits like a bindi on top of a woman’s forehead, perhaps, and the golden triangle becomes her nose. In one, the golden sun has risen, the shadow of the triangular mountain visible, very lightly, on a maroon-wine-brown colour field, as three bird-like half-moons approaches it in a vertical line. These acrylic on canvas works are at once evoke quietude and musical melodies, it could well be a mathematical riddle, a peculiar way of explaining the Pythagorean theorem, or a simple exploration of the earth, sky and everything beyond. The new solo show marks a fresh departure and an arrival in the artist’s oeuvre — from pale hues of his earlier works to a primacy of bold colours — with the triangle at its core and maturity in its articulation.

“It is an amazing phase in his own artistic career. What’s happening, according to me, in his work now is that there is a very audacious assertion, a very strong primacy of colour at one level. Second, it seems to be art which is all space without constraints or confines of time. Third, it has a quality. These geometrical shapes have a kind of autonomy. They don’t need any reference outside their own domain. They also defy verbal meaning. The visual meaning cannot be converted,” says poet and literary-culture critic Ashok Vajpeyi, “there is a certain element of maturity and a very sensitive and imaginative handling of the medium. The medium is now completely under his command, as it were.”

Art critic and historian Yashodhara Dalmia says, “It is interesting to note in S HarshaVardhana’s works the recurring motifs of geometric forms express a sense of movement which is further enhanced by the juxtaposition of these distinct forms and textures.”

S Harshavardhana's works at Art Alive Gallery, Delhi.

To look at HarshaVardhana’s paintings — floating or suspended triangles in a colour field — is to be reminded of the evocative visual aesthetic and the spiritual experience thereof of peering into a Mark Rothko painting and the Abstract Expressionism of his squares and rectangles. Rothko, while not a Bauhaus exponent, shared many stylistic and philosophical parallels — geometric shapes and bold use of colour. Different colours have different psychological effects. But it is the triangle by the Bauhausian Paul Klee, who used it as a fundamental shape to explore the relationship between form, colour and composition, that had struck a young HarshaVardhana.

And subconsciously, his father Swaminathan’s style has crept into his art. “The triangle is one,” says HarshaVardhana, adding, “When I was a teenager, in those days, art was being bought by foreigners and diplomats, whether Indians or not. Especially abstract art. So, there was a person in the Swiss embassy who became a good friend of my father. He gave me a small booklet on (artist) Paul Klee and when I opened it, the first thing I saw was a triangle, which hit me. And it has been seen in mathematics again. But the triangle has very symbolic value as well. In Christianity, it is supposed to represent the Holy Trinity and in Hinduism, upward-pointing triangle is purusha (man) and downward-pointing is prakriti (nature), both superimposed is the cosmos and creation. But the works are not about that. It’s just to demarcate some space and fill it with some other colour. I have used other forms like the circle, but throughout I’ve always liked the figure of the triangle. Triangle is my favourite form.”

As a child or in his teen years, he’d paint portraits but those didn’t sit well with him. “There is some mystery involved in this (abstract art). And that mystery is not only for me. Once I put it on the wall, I try to get detached. It is for the observer,” he says.

“My father once told me, ‘Harsha, the experience of making love is one and the experience of the child is another.’ So, these are the works of that experience of making love which I’ve enjoyed and now if you have any questions, you address them to the works, and hopefully, they’ll answer,” chortles the painter.

Becoming an artist, however, was never on the radar for the now-former bioscientist, who made a “very conscious” decision to stay away from art for the longest time.

S HarshaVardhana Untitled acrylic on canvas works.

“I had such good parents. They never interfered in my life. I passed out of school, Delhi Tamil Education Association, in 1974, with very good marks, 85 per cent. When I returned home, a very important artist and art teacher KG Subramanyan, at that time the Dean in Baroda [of the Faculty of Fine Arts at Maharaja Sayajirao (MS) University of Baroda], was sitting at home and he told my father to send me to MSU. My father looked at me and asked: you want to go to Baroda? And I blurted out, ‘I don’t want anything to do with art.’ Then I went on to do my master’s in bioscience and math. I left home and studied at BITS Pilani. By the time I returned from Pilani, my father had moved to Bhopal, where he set up that museum (Roopankar Art Museum at the multi-arts centre Bharat Bhavan). In the late ’70s-early ’80s, I started working and living in a varsity in Faridabad,” says the Delhi-based artist.

HarshaVardhana only became a full-time artist in 1993, aged 35. His first solo exhibition was in 1997 at Delhi’s Vadehra Art Gallery — which was in the eye of a storm last week when Delhi-based poet-activist Aamir Aziz accused the renowned contemporary artist Anita Dube for exhibiting and selling her works which plagiarised his widely known protest poem Sab Yaad Rakha Jayega at the gallery. Pablo Picasso had said, “Good artists copy, great artists steal.”

It isn’t like taking an image or figure or shape and giving it your own signature twist. Like geometric shapes, such as the triangle, that run as a leitmotif in the works of Abstract artists.

S HarshaVardhana at work.

“Look at these paintings, despite the recurring triangles, each is different from the next one to it,” HarshaVardhana tells me, while explaining his new move towards bright colours in his latest works — away from the pale hues he played with previously. “The interplay of colour and form in Harsha’s body of work is reassertion of the primacy of colour as well as discovery of space that his art discovers and creates. It goes beyond time, it is art as space unconcerned with or unconstrained by time,” adds Vajpeyi, as HarshaVardhana adds, “My palette has been changing and evolving. I never follow any kind of colour theory because there are some colours which should not be put beside each other. In fact, my hands take over, my brain is blank before I approach the canvas. I don’t start with something in my head and try to make an image of it. There is no story, no messaging. I’m not trying to send a message to society. I’m not trying to reform society. Nothing of that.”

What, then, is art’s role? “It is one of the necessities of life,” says the 67-year-old artist, who is on dialysis.

Vajpeyi points at two ways in which Swaminathan’s influence makes itself apparent in HarshaVardhana’s work, besides the triangle and bold colours. “Swaminathan used to talk about not the image of reality but the reality of the image. There is a strong sense of image [in HarshaVardhana’s works]. The image itself is real. It does not depend on any outside reference. Poetry has this curse of being meaningful. Meaning is a curse because you can’t have total abstraction in poetry because the words have meanings and they carry that along. But colours and shapes need not have any fixed meaning, so they have the freedom which poetry doesn’t have.” Dalmia adds, “The person who is looking at me is imbibing it with meaning which has to do with his own memory, experience, and his own projection.”

(From left) Art historian and critic Yashodhara Dalmia, artist S HarshaVardhana and poet and literary-culture critic Ashok Vajpeyi; a work by the artist.

I ask the artist whether the title of the show, “Subliminal”, which pertains to cognitive science and human perception, has to do anything with the subconscious and bioscience. He says, “The title is not given by me, I’ve forgotten about bioscience.” But he goes on to tell me how art is not far removed from it. “When you look at a blood clot under the microscope, it looks like a Jackson Pollock painting to me.” Pollock is known for his “drip technique” of splashing liquid paint on horizontal surfaces.

“My brain doesn’t know what my hands are doing,” says HarshaVardhana, “I don’t conceive the work first and try to make an image of it. The selection of colours is instinctive. I cover the surface with one colour to start with and then look at the palette and whatever colour there are, I pick up another colour and sometimes, it works. Sometimes, it doesn’t. So, I put another colour and keep layering it. That is my process, how my art progresses.” Earlier, he used to paint only one painting at a time, but this time in particular, since there are small canvasses, he tackled “two, three, four canvases simultaneously. When I was doing them one at a time, I used to get stuck at times and then I would put them under my bed and then re-address them after a period of time, say, six months later or so. In the interim, I painted other works,” he says.

I nudge him to tell me why the art collective Group 1890 — led by his father J Swaminathan, started in 1962 in Bhavnagar, which survived very briefly, unlike other art movements like the Bombay Progressives — disbanded? HarshaVardhana says, “When two artists sit together, they might start off amicably but they always have fights. It’s not easy to carry on. Here, they were all very temperamental. Like Jeram Patel didn’t like Rajesh Mehra or Gulammohammed Sheikh didn’t like somebody else, or my father didn’t agree with someone, so on and so forth. Then it just disbanded.”

As a child, at his home, he would quietly sit and listen to all these artists talk. Among his dad’s friends, HarshaVardhan was close to Ambadas and was drawn to his work. “Even as a man, my father was not very bothered whether I’m going to school or not. Ambadas used to take care of us, take us to watch a film when he was in Delhi. And then he married Hege [Backe] and they went to Oslo. I was very close to Ambadas at one time. And there’s Rajesh Mehra ji, who was a very reserved person. He wouldn’t talk much, but he was also close to us. Also very close to us was Himmat Shah, who stayed in our house, you know, when he shifted from Ahmedabad, before shifting to Garhi, which was actually my father’s studio. When my father left it, he gave it to him. Himmatji was also a very reserved man. But he was a very affectionate person,” says HarshaVardhana, who’s still reeling from the sudden demise of Himmat Shah last month. “I was shocked, but he lived a good life. Indian art is always in a flux. If someone passes away, somebody else comes in,” he says.

S Harshavardhana with his works at Art Alive Gallery, Delhi.

Subliminal, April 7-May 20, 11 am-7 pm, Art Alive Gallery, Panchsheel Park, Delhi. Closed on Sundays.

Discover the latest Business News, Budget 2025 News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

${res.must_watch_article[0].headline}

Sensex Today RIL Q4 Results 2025 Jammu Kashmir News Live CSK vs SRH Live Score Chris Wood HDFC Securities Asaduddin Owaisi Manipur HS Result KTET Result 2025 IPL Points Table 2025

Business Markets Stocks India News City News Economy Mutual Funds Personal Finance IPO News Startups

Home Currencies Commodities Pre-Market IPO Global Market Bonds

Home Loans up to 50 Lakhs Credit Cards Lifetime Free Finance TrackerNew Fixed Deposits Fixed Deposit Comparison Fixed Income

Home MC 30 Top Ranked Funds ETFs Mutual Fund Screener

Income Tax Calculator EMI Calculator Retirement Planning Gratuity Calculator

Stock Markets

News18 Firstpost CNBC TV18 News18 Hindi Cricketnext Overdrive Topper Learning

About Us Contact Us Advisory Alert Advertise with Us SupportDisclaimer Privacy Policy Cookie Policy Terms & Conditions Financial Terms (Glossary) Sitemap Investors

You are already a Moneycontrol Pro user.